From St Vedast, north along Foster Lane, past Goldsmith's Hall, and right into Gresham St. - past all those slick temples of Mammon - and St Lawrence Jewry next Guildhall.

Friday, 26 January 2024

Back in London: The City cont'd

Wednesday, 24 January 2024

Back in London: St Vedast, Foster Lane

St Vedast2, though in origin Medieval, is a Wren

church, but built some years after the Great Fire when the Medieval church

(patched up post-Fire) finally gave up the ghost. Other names have been

associated with rebuilding; in particular, Nicholas Hawksmoor who, as Sir John

Summerson put it, 'we may suspect had a hand in the interpretation' 0f the

spire. Kerry Downes in his biography of Hawksmoor for Thames & Hudson

says nothing. Anyway Wren's church has a nave and s aisle, separated by

an arcade of Doric columns. There is no chancel as such.

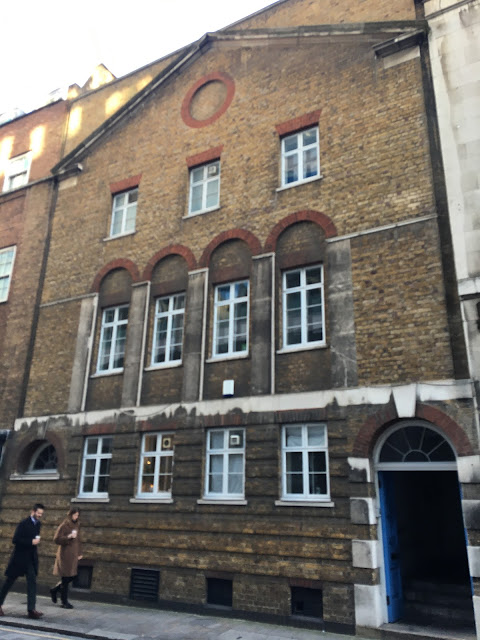

The church is quite hemmed in by buildings - there is no

churchyard. The only two walls to the street are the w on Foster Lane (ashlar)

and to the s. This s wall is very interesting - the furthest section w is the

base of the tower and is ashlared, the next section is of brick, the rest of

rubble stone. No doubt this wall wasn't meant to be seen; I wonder if it

is in fact Medieval? Of the other two walls, n and e, both are plastered. To

the n of the church is a small and charming 17th century vestry hall and, on

Foster Lane, the formidable looking rectory3 designed by

Dykes Bower. Dykes Bower linked these two buildings with a two storey

classical cloister built against the n wall of the church. The ground

floor is open, the glazed upper floor designed as a library. The

resultant courtyard is the most charming of spaces. A real hidden

treasure.

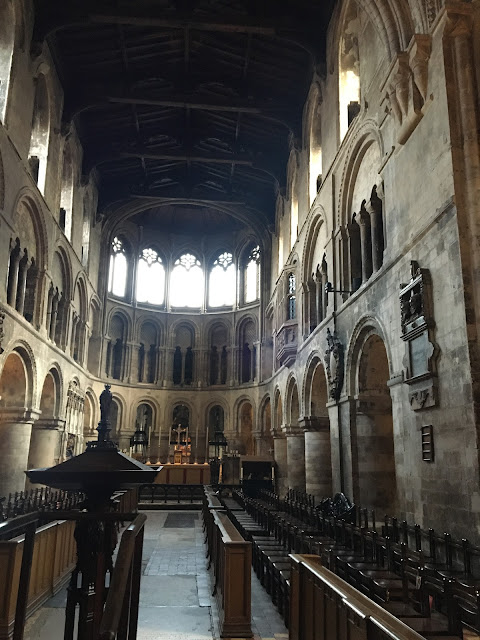

The interior is a faithful reconstruction of the original architecture.

Of the furnishings, Dykes Bower skilfully mixed old and new: the organ loft was

rebuilt; the altarpiece, pulpit and font cover garnered from other City

churches that had either been bombed or previously demolished - there was no attempt,

for instance, to recreate the original altarpiece A new marble floor, and new

stained glass designed by Brian Thomas (who had worked with Dykes Bower at St

Paul's) were installed and, finally, the nave re-seated collegiate style, that is with banks of stalls facing each other across the nave rather than

orientated toward the altar. The s aisle was made into a side chapel. The

result is excellent. The space coherent and lucid.

Looking round that morning I came across an intriguing Baroque

sculpture high up on the w wall of the s aisle. It depicts the Holy Spirit in

the form of a Dove surrounded by the shekinah, the Uncreated Light of

God, and cherubs. It's really rather fine. Turns out it is a tympanum and

was made to fit into the head of the middle window of the e end, making it a

rather more sophisticated version of the dove on the St Martin Ludgate

altarpiece in my previous post. The current altarpiece here at St Vedast, which

was originally from the demolished St Christopher-le-Stocks, also contains a

depiction of the Shekinah (with the Tetragram) in its pediment

to signify that the altar is the resting place of the divine, just as the

tympanum signifies the descent of the Holy Spirit on the unconsecrated

elements, the bread and wine, in the Eucharist to make them the Body and Blood

of Christ.

The poet Robert Herrick was baptised in St Vedast's on 24th August

1591

Monday, 22 January 2024

Back in London: The City

Thursday, 18 January 2024

Back in London: The National Gallery

Monday, 15 January 2024

'The Driver's Seat'

The Driver's Seat

1974

Cinematogrpahy Vittorio Storaro

Producer Franco Rossellini

Sunday, 14 January 2024

Back in London: The York Water-gate

Well, back to London this last week. We were heading there to see a production of Stephen Sondheim's 'Pacific Overtures' at the Menier Chocolate Factory. However, due to family illness that fell through, and I sadly made a solitary visit to the capital.

Built in 1626 of Portland Stone using the masculine Tuscan Order, the gate was designed as a monumental entrance to York House from the river.* (There would have been some sort of pier or landing stage on the river side.) To the landward side the architecture is 'polite', or 'dilicate' as Serlio would have it, after all it faced the gardens and the house; to the river in contrast all is drama and bold rustication. And that is the side I prefer.