I took the opportunity when walking around Cambridge in November to pop in and take some photos of St Botolph's church for this blog. A slightly forgotten church, St Botolph's. Typical of Cambridgeshire; like Hertfordshire and indeed most of SE England, a 'small stone' county. The walls here are constructed of rubble masonry, a mixture of Upper Jurassic Barnack Rag (a type of ooltic limestone) and the relatively local Carrstone - there may also be some local chalk in the mix. Some of the Carrstone, in the form of cobbles, looks like it has been garnered from Glacial Till (the geological phenomena formerly known as 'Boulder Clay') or alluvial deposits. These stones collected from from the Till are known as 'Fieldstones'. The Till itself forms the 'Western Plateau', the extensive area of 'high' land just to the west of Cambridge. The mouldings to windows and doors etc. are also of oolitic limestone, perhaps of Barnack Rag though there the best quality stone was worked out by 1460. Unlike the local chalk and the Carrstone (which in addition is also difficult to work) the Ragstone is not only easy to carve and much more durable. However, unlike the chalk and Carrstone, ooltic limestone is not indigenous to Cambridgeshire but had to be brought across the Fens in barges from the Limestone Belt, from quarries in Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire and Rutland.

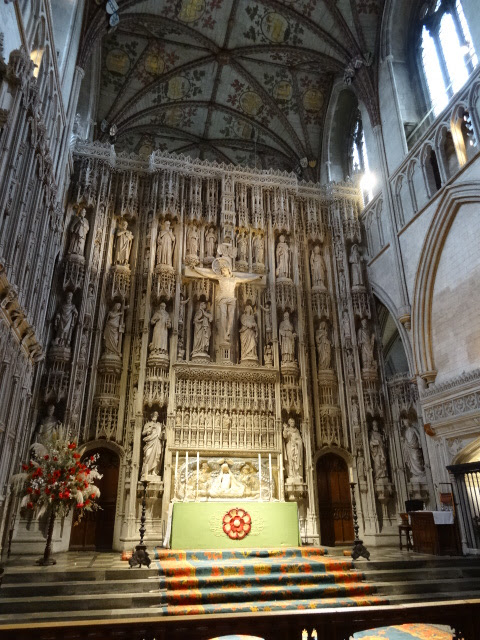

Enough of the geology! The exterior of the church is mainly Late Gothic - the chancel is Victorian, by George Frederick Bodley. The darker colour of the wall seems rather insensitive, particularly from an architect such as Bodley. The texture of the Medieval walls is very satisfying. Inside all is light, and a little austere rather like one of those 17th century Dutch paintings of a church interior. The arcades date, according to the good Doktor (aka Pevsner) to the early 14th century, so Decorated then. Bodley's rebuilt chancel dates from 1872 and is dark with colour and stained glass. The contrast with the nave, I think, too stark. The panelled ceiling is rather pretty though. The rood screen is late medieval and there is a Royal Arms under the tower, but the treasure of this church is the Laudian font cover - all attenuated Jacobean classicism and marbling. Rather fun.