Just a few pages from my latest sketch book. Mixed media one and all.

Tuesday, 31 October 2017

Sunday, 29 October 2017

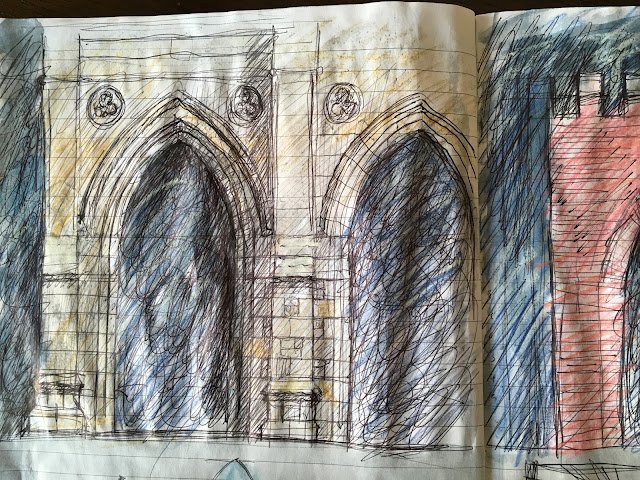

Ss Peter and Paul, Tickencote

I consider myself very blessed to live close to some very beautiful towns, villages and countryside. Yesterday, on a brilliant Autumn day I made a return visit to Tickencote in Rutland. I hadn't been there in years, since in fact I was a small child. It really is an exquisite place, a small stone built village, with a marvellous church. The visit only confirmed that the local oolitic limestone looks better in slanting Autumn light. It seems then to posses a beauty that makes my heart ache.

St Peter and St Paul is jewel of a church. Small, neat and perfectly formed. It is the work of two periods hundreds of years apart - Norman and Georgian. Both are worth seeing on their own merits, but the Norman work steals the show with some pretty spectacular architecture for a humble village church. The exterior is however Georgian. Not classical but Neo-Romanesque, the work of Samuel Pepys Cockerell. The chancel is a restoration of the original Norman, the nave and the tower & vestry (which project like transepts from the e end of the nave) are wholly the design of Cockerell and are built of the smoothest Neo-classical ashlar. All of dates from the early 1790s when Cockerell was called into restore the dilapidated Medieval church by Miss Eliza Wingfield. Cockerell swept away all the later Medieval work, retained the sumptuous Norman chancel and attempted in his new work to harmonize with the old. The result is at times extraordinary if not bizarre, such as the arch into the porch under the tower. His plan, I think, owes a lot to that of Cormac's Chapel on the Rock of Cashel, County Tipperary, Ireland.

Cockerell's interior is simple and rather noble, making no attempt to compete with the Norman chancel which is on a scale and sumptuousness that is more suited to a cathedral rather a remote country church. An embarass du richesse. The chancel is vaulted with a sexpartite vault (that is six ribs and six webs) - a rare thing for its date, but what stays in the imagination is that incredible chancel arch, not only is it on a gargantuan scale, with the most wonderful enigmatic carvings but it has buckled and deformed with the years in the most alarming manner. Extraordinary, and a treasure.

St Peter and St Paul is jewel of a church. Small, neat and perfectly formed. It is the work of two periods hundreds of years apart - Norman and Georgian. Both are worth seeing on their own merits, but the Norman work steals the show with some pretty spectacular architecture for a humble village church. The exterior is however Georgian. Not classical but Neo-Romanesque, the work of Samuel Pepys Cockerell. The chancel is a restoration of the original Norman, the nave and the tower & vestry (which project like transepts from the e end of the nave) are wholly the design of Cockerell and are built of the smoothest Neo-classical ashlar. All of dates from the early 1790s when Cockerell was called into restore the dilapidated Medieval church by Miss Eliza Wingfield. Cockerell swept away all the later Medieval work, retained the sumptuous Norman chancel and attempted in his new work to harmonize with the old. The result is at times extraordinary if not bizarre, such as the arch into the porch under the tower. His plan, I think, owes a lot to that of Cormac's Chapel on the Rock of Cashel, County Tipperary, Ireland.

Cockerell's interior is simple and rather noble, making no attempt to compete with the Norman chancel which is on a scale and sumptuousness that is more suited to a cathedral rather a remote country church. An embarass du richesse. The chancel is vaulted with a sexpartite vault (that is six ribs and six webs) - a rare thing for its date, but what stays in the imagination is that incredible chancel arch, not only is it on a gargantuan scale, with the most wonderful enigmatic carvings but it has buckled and deformed with the years in the most alarming manner. Extraordinary, and a treasure.

Friday, 27 October 2017

Thursday, 26 October 2017

A Saturday in Cambridge: Edgar Degas and Ivan Mosjoukine

To an unbelievably busy Cambridge on Saturday afternoon. Our first stop was the Fitzwilliam Museum and the Degas Exhibition. It too was crowded. Coupled with the richness on display I'm inclined to make a return visit on a weekday.

The work of Degas does need some thought, some contemplation; he was a painter, printmaker, sculptor and poet*. He also studied photography. A complex artist then with a proper breath of interests. A restless, enquiring mind too one would guess. In 1855, abandoning a law degree, he entered the studio of Louis Lamothe, who had been a pupil in turn of Jean-Auguste-Dominic Ingres, his great hero, enrolling also in the Ecole des Beaux Arts. Although easy to see the Beaux Arts system as stultifying it did give students a thorough knowledge of the craft of drawing and painting. Without such a background it seems hard to conceive of Degas producing the work he did. Politically he was an ultra conservative, Royalist and reactionary, with a deep distrust, like Auguste Renoir, of Modernity and Socialism.

'Drawing', wrote the late, great Peter Fuller, 'was key to Degas's art.' And the emphasis of this exhibition, which is laid out sequentially, is on work on paper, in the main drawings, and the female form. Less space is dedicated to Degas, the painter of horses and of landscapes, and to Degas the sculptor but there is a copy, in bronze, of the decidedly creepy 'Little Dancer of Fourteen Years'. Enough really to give a rounded portrait of Degas the artist. There are also a small number of oils dotted around the exhibition, including the terrible 'Art of Warfare in the Middle Ages', young Degas's attempt at a history painting. However there are, in the 2nd gallery, a small group of oils of a completely different quality which Degas painted of women in some kind of communication or other. They are exquisite in the manner in which they capture a fleeting moment of contact between two people. This group of oils forms a hinge, as it were, in the exhibition, a moment of transition leading to the 3rd and largest gallery which is given over to Degas's drawings of ballet dancers and solitary bathing women. Reading up for this blog I've come across critics saying that Degas wasn't interested in his subjects as people merely as a vehicle for his interest in colour, form and movement. After seeing this exhibition I really begin to question this. The interplay of people in these paintings and drawings seems just as important to me as any play of light or colour; the German painter, Max Liebermann, spoke of Degas's ability to convey an 'impression of a fleeting moment of time'. I have to confess I didn't much like Degas's drawings of solitary bathers, with exception of the woman drinking coffee beside her bath. Subsequently I found a quote from the film maker Jean Renoir, son of August Renoir, that perhaps has resonances with the work of Degas. Renoir fils recalled hearing his father talking of 'that state of grace which comes from contemplating God's most beautiful creation, the human body.'

One of the aims of the exhibition is to place Degas within an art historical context, and to this end the work of his contemporaries, particularly those he admired, punctuate the exhibition; and there is some very interesting work on display, mostly small scale and some rather jewel like. Those rich nineteenth century colours are wonderful. In addition to a bright paintings of apples by Cezanne, look out for the Corots, a beautiful group portrait (in pencil) by Ingres, and two monumental life studies by Cezanne and David. Both the convey the deep beauty and heft of the male form.

The final section demonstrates his influence on subsequent British art. There is work (amongst others) by Moore, Auerbach, Sickert, Bacon, Freud and Hockney - a lovely pencil-crayon drawing of Celia Birtwell. The Freud was stunning and I liked the Bacon more than I thought I would.

Then out the door and up the street. It is the Cambridge film festival, but in our chronic inability to be organised we only saw one film. It was however a real corker: 'The Loves of Casanova'. It starred the émigré Russian actor Ivan Mosjoukine.

'Drawing', wrote the late, great Peter Fuller, 'was key to Degas's art.' And the emphasis of this exhibition, which is laid out sequentially, is on work on paper, in the main drawings, and the female form. Less space is dedicated to Degas, the painter of horses and of landscapes, and to Degas the sculptor but there is a copy, in bronze, of the decidedly creepy 'Little Dancer of Fourteen Years'. Enough really to give a rounded portrait of Degas the artist. There are also a small number of oils dotted around the exhibition, including the terrible 'Art of Warfare in the Middle Ages', young Degas's attempt at a history painting. However there are, in the 2nd gallery, a small group of oils of a completely different quality which Degas painted of women in some kind of communication or other. They are exquisite in the manner in which they capture a fleeting moment of contact between two people. This group of oils forms a hinge, as it were, in the exhibition, a moment of transition leading to the 3rd and largest gallery which is given over to Degas's drawings of ballet dancers and solitary bathing women. Reading up for this blog I've come across critics saying that Degas wasn't interested in his subjects as people merely as a vehicle for his interest in colour, form and movement. After seeing this exhibition I really begin to question this. The interplay of people in these paintings and drawings seems just as important to me as any play of light or colour; the German painter, Max Liebermann, spoke of Degas's ability to convey an 'impression of a fleeting moment of time'. I have to confess I didn't much like Degas's drawings of solitary bathers, with exception of the woman drinking coffee beside her bath. Subsequently I found a quote from the film maker Jean Renoir, son of August Renoir, that perhaps has resonances with the work of Degas. Renoir fils recalled hearing his father talking of 'that state of grace which comes from contemplating God's most beautiful creation, the human body.'

One of the aims of the exhibition is to place Degas within an art historical context, and to this end the work of his contemporaries, particularly those he admired, punctuate the exhibition; and there is some very interesting work on display, mostly small scale and some rather jewel like. Those rich nineteenth century colours are wonderful. In addition to a bright paintings of apples by Cezanne, look out for the Corots, a beautiful group portrait (in pencil) by Ingres, and two monumental life studies by Cezanne and David. Both the convey the deep beauty and heft of the male form.

The final section demonstrates his influence on subsequent British art. There is work (amongst others) by Moore, Auerbach, Sickert, Bacon, Freud and Hockney - a lovely pencil-crayon drawing of Celia Birtwell. The Freud was stunning and I liked the Bacon more than I thought I would.

Then out the door and up the street. It is the Cambridge film festival, but in our chronic inability to be organised we only saw one film. It was however a real corker: 'The Loves of Casanova'. It starred the émigré Russian actor Ivan Mosjoukine.

Mosjoukine (French transliteration) was part of the culturally rich and important Russian community that formed in Paris after the 1917 Revolution. Think music, theology, literature and theatre and cinema. The director was another émigré: Alexander Volkov. It is a lavish historical epic. I'm almost inclined to call it a romp, but such a word wouldn't do it proper justice. The highlights for me, at least, were the crowd scenes filmed on location in Venice. Superb. The hand coloured scene set upon a Venetian canal full of gondolas - breath taking. In all very satisfying. Look out for actress Diana Karenne with her haunting fin-du-siècle looks, as though she had stepped out from a painting by Ferdinand Knopf.

* Degas's poetry, mainly in sonnet form, is discussed, I think, in Paul Valery's 'Degas, Danse, Dessin' (1938).

* Degas's poetry, mainly in sonnet form, is discussed, I think, in Paul Valery's 'Degas, Danse, Dessin' (1938).

The Loves of Casanova

1927

Producer: Noe Bloch, Gregor Rabinovitch

Director: Alexandre Volkov

Cinematographer: Fedote Bourgasoff, Leonce-Henri Buel, Nicholi Toporkoff

Labels:

'Casanova',

Cambridge,

Edgar Degas,

exhibitions,

Film,

Ivan Mosjoukine,

Reviews

Tuesday, 17 October 2017

Own work: Life Drawing XLV

Last week's drawings - a rare three drawing day. Two half hour poses, followed, after the coffee break by a single hour long pose.

Monday, 16 October 2017

Friday, 6 October 2017

Ickworth II

Ickworth is now in the hands of the National Trust, the old family wing a hotel. The incomplete western wing, very sensibly, is now the reception and café. The entrance lobby is spoilt by painted quotes, in the way that the National Trust seems to be fond of today. Alas. However the long thin orangery is just right. The Lloyd Loom furniture hits just the right note of timelessness. Perfect. It could have be the Edwardian age or the 1920s, but I liked to think it was the early Seventies and that any moment Celia Birtwell and David Hockney were going to step in from the garden. A few floor standing uplighters between the windows would add a little more glamour, but anything else would spoil it.

To the south of the house there is a Victorian Italianate garden bounded with a great bastion of a wall complete with gravel walk. It effectively separates the house from the landscape park beyond - which is the work of Capability Brown and one of his duller numbers. Down in the valley is a lake and between it and the house is the old village church and a large walled garden which is in a sorry state at the moment but there are signs of restoration. The summer house is a delight. The church is small and neat. The tower, I think, is late 18th/early 19th century, stuccoed, and the rest of the church looks entirely Victorian, but is I think, almost a replica of what was there before - note the squint into the chancel. It is the traditional resting place of the Herveys, but, alas, on our visit the church was locked.

To the south of the house there is a Victorian Italianate garden bounded with a great bastion of a wall complete with gravel walk. It effectively separates the house from the landscape park beyond - which is the work of Capability Brown and one of his duller numbers. Down in the valley is a lake and between it and the house is the old village church and a large walled garden which is in a sorry state at the moment but there are signs of restoration. The summer house is a delight. The church is small and neat. The tower, I think, is late 18th/early 19th century, stuccoed, and the rest of the church looks entirely Victorian, but is I think, almost a replica of what was there before - note the squint into the chancel. It is the traditional resting place of the Herveys, but, alas, on our visit the church was locked.

Tuesday, 3 October 2017

Own work: Life Drawing XLIII

One drawing from last weeks class (two poses were planned but model was a little unwell due to her condition, and a new pose had to be created for her!)

Monday, 2 October 2017

Ickworth I

A spur of the moment thing our trip to Ickworth, and well worth it. The house is a stunner, and also, almost unique. Coincidental too, considering my current fascination with the cultural efflorescence of the Protestant Ascendancy that ruled Ireland for a hundred years or so following the Glorious Revolution. (Perhaps more of that in a further post.) And perhaps it is with the Irish connection that I should begin.

The builder of Ickworth was Frederick Hervey (1730-1802), 4th Earl of Bristol, Lord Bishop of Derry. (The estate at Ickworth had been the hands of the Hervey's since the 15th century.) As was common for a younger son Hervey entered the church, though his faith seems to have been somewhat lukewarm. He achieved preferment however and when his older brother became Lord Lieutenant of Ireland he was elected Bishop of Cloyne. After a year he became Bishop of Derry, and as such he enjoyed a sizeable yearly income. I have to confess that I don't warm to the Earl-Bishop - an apparently volcanic temper, most likely a Deist if not an agnostic but happy to have church preferment. A man of contradictions, perhaps, even hypocrisy. It's hard not to see him, at least, as cynical. Worldly, certainly. However, it's hard not to warm to him as artistic patron.

The builder of Ickworth was Frederick Hervey (1730-1802), 4th Earl of Bristol, Lord Bishop of Derry. (The estate at Ickworth had been the hands of the Hervey's since the 15th century.) As was common for a younger son Hervey entered the church, though his faith seems to have been somewhat lukewarm. He achieved preferment however and when his older brother became Lord Lieutenant of Ireland he was elected Bishop of Cloyne. After a year he became Bishop of Derry, and as such he enjoyed a sizeable yearly income. I have to confess that I don't warm to the Earl-Bishop - an apparently volcanic temper, most likely a Deist if not an agnostic but happy to have church preferment. A man of contradictions, perhaps, even hypocrisy. It's hard not to see him, at least, as cynical. Worldly, certainly. However, it's hard not to warm to him as artistic patron.

In Ireland Harvey built, almost concurrently, two large houses: Downhill, built romantically upon a cliff top in County Londonderry, and Ballyscullion in County Antrim. It's really the folly he had built at Downhill by Michael Shanahan of Cork - the Mussenden Temple - and Ballyscullion that are important here, for both, like Ickworth, are rotundas. Alas, Ballysullion, like the house at Downhill, has perished, but from surviving drawings it is clear that it was very close to Ickworth in design - a central rotunda, with a pedimented temple front (think the Pantheon in Rome), linked to flanking wings by curving colonnades.

The architect of Ballyscullion is not known for certain, but the design has been linked to Francis Sandys who was in m'Lord Bishop's household - his brother was the Earl-Bishop's chaplain. (Any number of architects are connected to Downhill - the Sardinian Davis Ducart, Soane, Wyatt and Charles Cameron - but the executant architect is most likely to have been Shanahan.) A similar confusion hangs over the design of Ickworth; but it is however believed that the design originates with the 'Italian' Mario Asprucci the Younger, the executant architect being Francis Sandys. However, as I have said, the house is so similar to that at Ballyscullion that it's hard not to think that Sandys had more a hand in the design than he is usually credited with. Perhaps both Asprucci and Sandys were only actualising Frederick Hervey's ideas and that the design is essentially his.

The house was begun in 1795, by which time the Earl-Bishop, with entourage, had left Ireland for good and was on another Grand Tour. By then he had inherited Ickworth and the Hervey titles, so he had two income 'streams' and was very rich indeed. Alas, m'Lord Bishop of Derry died with the house incomplete, and having never seen it. It had been destined to hold his vast art collection but that had already been confiscated by Napoleon. The shell of the house wasn't completed until 1830, by John Field, and the western wing was never fitted out as intended, but then without the art it was rather purposeless, and the east wing which, I think, was destined to be the library, became the family wing.

What was realised, however, is very impressive. The central rotunda is vast - 100 feet to the top of the dome, each order is 30 feet high - and very satisfying. It has great heft and presence that is sometimes lacking in contemporary English architecture (compare it to Heveningham by Taylor, also in Suffolk). Like the rotunda at Bullyscullion it is decorated with half-orders - two orders here though, Ionic below, Corinthian above, executed in stone. The walls, of brick, are coated in stucco. The two friezes, of terracotta and Coade stone, are the work of Casimiro and Donato Carabelli of Milan.

What was realised, however, is very impressive. The central rotunda is vast - 100 feet to the top of the dome, each order is 30 feet high - and very satisfying. It has great heft and presence that is sometimes lacking in contemporary English architecture (compare it to Heveningham by Taylor, also in Suffolk). Like the rotunda at Bullyscullion it is decorated with half-orders - two orders here though, Ionic below, Corinthian above, executed in stone. The walls, of brick, are coated in stucco. The two friezes, of terracotta and Coade stone, are the work of Casimiro and Donato Carabelli of Milan.

The wings are huge in themselves. I detect in them a touch of the Baroque, just as there is in the curve and countercurve of rotunda and colonnade. That shouldn't surprise. Italy went straight from Baroque to Neoclassical and the Irish Neo-Palladianism was always rather baroque inclined. It begs the question though: just how Irish is Ickworth? A question I can't answer.

The interior is very monumental, the principal rooms are very high and there great columns of scagliola in the Saloon and entrance hall. But it is all a little plain. The principal stair threads its way up through the architecture as though it was designed by Vanbrugh or Hawksmoor. Its current form however is Edwardian and is the work of Arthur Blomfield, viz Oundle. My favourite parts were the corridors leading to the wings, which seem to be fully commensurate with the exterior. The east corridor is particularly fine. Alas the Pompeiian room (very late, by J G Grace, viz Algarkirk) was closed for restoration. I was looking forward to that.

The interior is very monumental, the principal rooms are very high and there great columns of scagliola in the Saloon and entrance hall. But it is all a little plain. The principal stair threads its way up through the architecture as though it was designed by Vanbrugh or Hawksmoor. Its current form however is Edwardian and is the work of Arthur Blomfield, viz Oundle. My favourite parts were the corridors leading to the wings, which seem to be fully commensurate with the exterior. The east corridor is particularly fine. Alas the Pompeiian room (very late, by J G Grace, viz Algarkirk) was closed for restoration. I was looking forward to that.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)