There are also outwardly built three Pyramids, or steeples of a good convenient height, all very well wrought with Free Stone and especially the two Gemmets that stand westwards, very well cut and cureously wrought. The which West Part is [] exceeding finely and cunningly set forth, with a great number of Tabernacles, and in the same, the Images or Pictures of the Prophets, Apostles Kings of Judah, and divers other Kings of this Land, so well embossed and so lively cut, that it is a great pleasure for any man that takes delight to see such Rarities, to behold them.

It was a relief to leave the city centre of Birmingham and head through some interesting and leafy suburbia north to Lichfield, in the unregarded county of Staffordshire. An all together different city; Defoe described it as "a place of conversation and good company"; it was after all the place of Dr Johnson, David Garrick, Erasmus Darwin and Anna Seward, a place of sensibility. It was my second visit and the bf's first, and the place is a delight - busy and prosperous. The centre is compact, dense and hierarchical. It was market day too, which is always a good thing, though not so good for the photography! Lichfield is a planned medieval town, c1140, built to the south of the cathedral. The site though is of greater antiquity. Close to Repton and Tamworth, it was one of the major centres of power in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Mercia. And perhaps possessing a still greater antiquity.

To the east of the city centre is St Michael, Greenhill. A medieval/Victorian church that stands in the midst of a vast graveyard. I believe it is the largest in the country. Mesolithic items have been found there, and legend links it to the persecution of the Christians under the Emperor Diocletian. Another credits the dedication of the cemetery itself to St Augustine of Canterbury and the Roman Mission. Whatever the basis of these stories, by the 8th century St Michael's had been endowed with vast landholdings. This has led some historians, such as Steven Bassett*, to suggest that St Michael's is the site of an important early Christian centre, possibly the seat of a British bishopric such as those at St Helen Worcester, and St Mary de Lode in Gloucester. It seems that the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons in the this part of the Kingdom of Mercia and the lower Severn valley was the work of the existing British populations, and not the Roman Mission.

The Kings of Mercia took their bishops from Northumbria and also Ireland. St Chad, the fifth bishop, was no exception. He is thought to have been born in what is now Yorkshire. His name is Brythonic, as are names of his three brothers - Cedd, Caelin and Cynibil. As was also the name of his assistant/servant Ovin, ie. Owain or Owen, who is said to be the same Ovin who was part of St Etheldreda's household. I wont describe Chad's earlier life in Northumbria except to say it is 'complex'. I don't mean 'problematic', only he was a very busy man, a bit restless maybe. It is enough here to know he, like his predecessors, was trained in the Irish monastic tradition in northern England and in Ireland itself. Chad's time in Mercia is subject to all sorts of legends and variants. It is thought he arrived c.669, but at one time it was believed he had arrived before that date and been living the eremitical life in part of Lichfield that is now known as Stowe, but what for centuries had been known as Chadstowe; attracted, perhaps, by the ancient sanctity of St Michael's church. Be that as it may Chad was appointed Bishop of Mercians c669 and was bishop for three years. It was he who, apparently, moved the cathedra from Repton to Lichfield. By his death there seems to have been two monasteries in Lichfield; St Chad's own skete at the site of St Chad's in Stowe (the church was then apparently dedicated to St Mary), and a second founded by the Mercian King Wulfhere. Chad was buried close to St Mary's church and remained there until c700 when his remains were translated to a new(?) cathedral church dedicated to St Peter on the site of the current structure, and which was situated within Wulfhere's foundation. I hope I've got that right!

And so finally to the cathedral itself. I can't do better than quote from the Buildings of England: "Lichfield is one of the smaller English cathedrals (371'), but it has two features which single it out from all others; its three spires and the Minster Pool and Stowe Pool assuring it of a picturesqueness of setting which none can emulate."

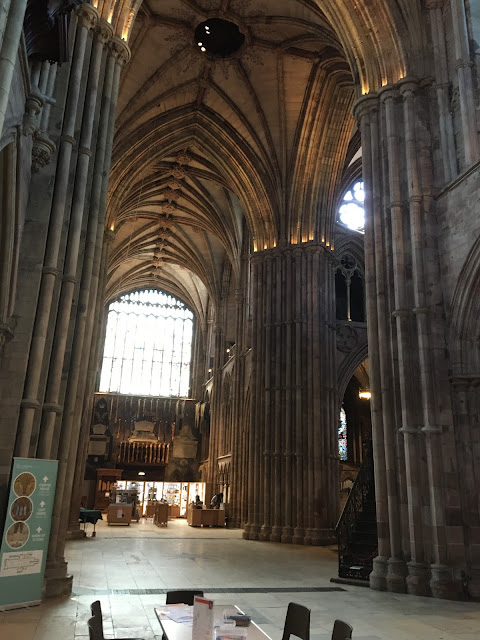

In fact the building (for a cathedral) is so low (for instance, the nave vault is less than 60 ft high) that it scarcely registers in the urban landscape at all. I should add that the central tower, which has some stylistic links to the central towers of Pershore and Worcester, is uncommonly short; I think the great spire that that rests upon it must account for half the total height, if not more.

It's only as you approach, and I suggest you approach from the west along Bird St, that the three stones spires - the 'Ladies of the Vale' - appear above the trees. It is only at the moment of turning into the close that the cathedral finally reveals itself to the visitor, all dark and spikey, the flat façade of the w end enmeshed in a dizzying net of tracery and statuary. For all its flaws, (and it does divide critical opinion), it is quite the spectacle. A proper coup du theatre.

At this point we step into the cathedral close - I've written about cathedral closes before now, but never explained them: a close is simple an enclosure, sometimes fortified, containing the cathedral and its ancillary buildings, such as housing for the cathedral clergy and staff. Here the close is neatly rectangular, unlike say Lincoln which is a very awkward shape and is intruded on too much by the modern world such as a main road. The close at Lichfield dates from the 1200s but I'd like to think that the boundaries are actually Anglo-Saxon. Though without the profound numinosity of the close at St David's, it is still a particularly attractive and peaceful place, and it contains some beautiful houses. Two buildings stand out for me: the Neo-classical austerity of Newton's College, and the rather French bishop's palace, dating mainly from the Restoration. It is has been credited to Edward Pierce (1630-1695) the mason/sculptor, who worked for Sir Christopher Wren. I should add here a note about what has been lost in the cathedral close: the gates have been demolished at some point, as has the late Medieval cathedral library (a half-timbered structure apparently. It is just visible on Hollar's engraving of the w front). In addition a chantry chapel has been demolished on the north side of the nave, and, intriguingly, depicted on two 19th century plans of the cathedral the location of the tomb chamber of the Mercian kings. Gerald Cobb in his fascinating book 'English Cathedrals: The Forgotten Centuries' mentions a free standing bell tower, but I've never seen that mentioned in any other book.**

'The Ladies of the Vale' make Lichfield quite unique amongst the medieval cathedrals of, not only England, but the British Isles. No other possesses, or has ever (as far as we know) possessed, three stone spires. But be not fooled though, for the central spire - the 'Rood Spire' - is not medieval but a 17th century reconstruction of the destroyed original. Even so Lichfield fared somewhat better in this regard than Ripon and Lincoln, both of which had three spires constructed of timber & lead and lost all over time. The two three spired cathedrals in Scotland, Elgin and Aberdeen, fared worse of all. All is Ichabod, or almost, for although the former is in complete ruins and the latter only a fragment - loosing choir, transepts and central tower & spire - it does retain the nave with its two w spires, built of intractable granite.

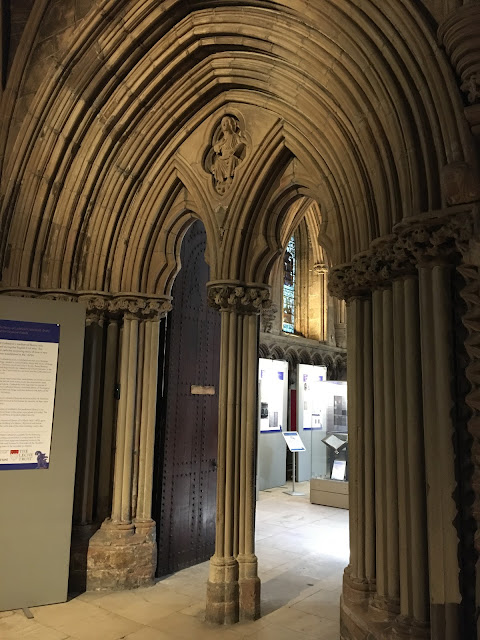

Lichfield is constructed, like the cathedrals of Worcester and Chester, of Triassic New Red Sandstone of varying intensity of colour from dark brown to pinky-grey. One imagines it, under certain weather conditions, to be a brooding, sombre presence. The great problem in using this stone is its susceptibility to weathering, hence the presence of scaffolding on the central tower in the following images. The result of this almost constant repair and replacement of stone is that in places very little of the original medieval stonework is left; this particularly true of the west front where virtually all of the visible masonry dates from the late 19th century, the work of Sir George Gilbert Scott and his son John Oldrid Scott; the figures sculpted by Robert Bridgeman & Son, except those around the Great West Door which are by Mary Grant. The waspish architectural historian Alec Clifton Taylor was rather sniffy about their work, saying the sculpture was "passable advertisements for the local hairdresser, every little wisp having been carefully 'set' in a fussy little curl."

In addition, as hinted to above, the cathedral suffered massive amounts of damage during the English Civil War when the close was held as a fortress alternatively by both sides. It was besieged three times. Canon fire brought down the central spire and destroyed the roofs. Puritans smashed anything considered idolatrous. The cathedral remained in a near derelict state until the 1660s when a restoration was undertaken under Bishop Hacket (the church was re-consecrated in 1668). When divine service had been resumed in 1660 services were held in the chapterhouse, the rest of the cathedral being in such a bad state of repair.

"June 16th, 1660. This morning Mr Rawlins, of Lichfield, told me that the Clerk Vicars of the cathedral had entered the chapter-house, and there said service; and this, with the vestry, was the only place in the church with a roof to shelter them."

Elias Ashmole ?

Not only was the spire rebuilt, but new window tracery inserted, vaults rebuilt and new furnishings supplied.

How much then does this lack of original work matter? And how, exactly do you conserve a building such as this? These are questions that are still 'live' in the worlds of architecture and architectural criticism. These thorough-going Victorian restorations have come in for much criticism since, but it can be argued that the very survival of these buildings depended on the thoroughness of our nineteenth century forebears. Perhaps it matters little for any changes embody the history of the building, and surely it cannot be expected that any building should or can survive intact for so long. A pragmatic approach is required, not a desire for purity.

* cf 'Church and Diocese in the West Midlands: The Transition from British to Anglo-Saxon Control' in 'Pastoral care before the Parish' ed John Blair and Richard Sharpe (Leicester, 1992) pp 13-40

** Doing a quick bit of research I found it mentioned in the original Bells Cathedral series volume on Lichfield. It was demolished in 1315.