And so passing to the right of the Rood Screen, and passing through the south choir aisle - past some attractive 18th century monuments and the site of the shrine of the two hermits Roger and Sigar - we enter into the beating heart, the engine room, of the cathedral. In this particular case there are two engines driving the spiritual life of this building: the choir & High Altar, and the reconstructed shrine of St Alban further east.

Suddenly, emerging from the dark, cave-like s choir aisle we step into a vast space: the transepts and crossing. All is Norman, tough and masculine. Austere and light filled. In the Middle Ages however we wouldn't have been able to experience this space in the same way: two walls would have partially obstructed the view through the crossing to the N transept, isolating the working space of the choir from the subsidiary transepts. And that returns me, briefly, to a theme from my last post - the contrast in perceptions of space in a building such as this over time. The rood screen was the first in a series of screens dividing the massive volume of the building into, perhaps, more manageable parts. The choir would have been isolated from the nave not only by the Rood Screen but by a second more massive masonry construction called a pulpitum and perhaps from the presbytery and the High Altar by a thinner wooden screen. There was, certainly a second rood beam at this point. It is highly likely also that an altar stood somewhere between the choir and the High Altar. All of this would have produced a deep spatial complexity (if not confusion), and perhaps a heightened sense of mystery. Only from above, high in the clerestory for instance, would the visitor have any sense of spatial unity which we tend to look for these days in our post-Reformation, post-liturgical movement and now post-religious world when aesthetics and historical sensibilities have as much, if not more, weight as the spiritual.

This spatial complexity is the result of a process outlined by the French architectural historian Alain Erlande-Brandenburg in his book 'The Cathedral: The Social and Architectural Dynamics of Construction'. The historical process is quite straightforward. In the post-Constantinian church it was the practice to give each of the various religious functions of a cathedral a distinct and independent architectural expression; for instance baptistries. We can see a similar process in the secular architecture of Late Antiquity eg 'Villa Romana del Casale' at Piazza Armerina on Sicily, or the Palace of Antiochus in Constantinople. The result was a complex of buildings such as you might find at Tebessa in N Africa. It can be seen today in several Orthodox monasteries and is also evident in Celtic and Anglo-Saxon monastic sites. The creation of the great abbeys and cathedrals of western Europe which begins with the Carolingian Renaissance and continued into the High Middle Ages witnessed the consolidation of those separate functions in one overarching architectonic expression in which those different uses were demarked with screens.

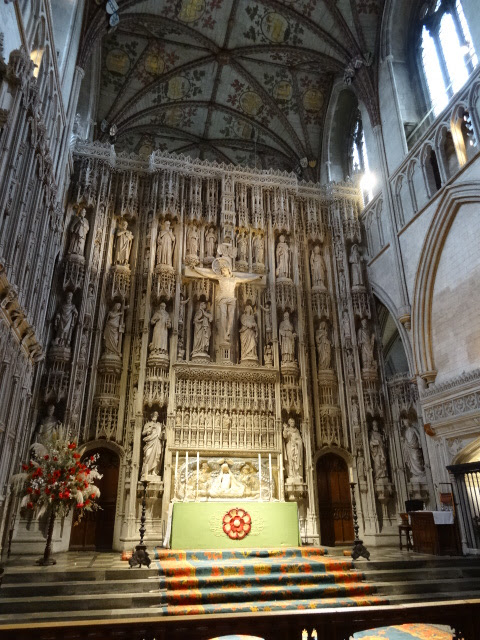

The presbytery is Dec Gothic, and rather good with tall clerestory windows. The wooden vault, and its Medieval decorative scheme, I love. The vast wall of the Wallingford Screen is Late Gothic, the current statuary is by Harry Hems, the originals having been destroyed at the Reformation. The panel directly above the High Altar is by the Art Noveau sculptor Sir Alfred Gilbert - quite strange I think, but as it isn't possible to get that close I will reserve judgement! On either side of the High Altar are Late Gothic chantry chapels. Dec too the ambulatory and the heavily restored Lady Chapel.

And finally to the shrine. I entered the shrine space by the narrow door in the N presbytery aisle. It is an 'intense' space, cramped and vertiginous. I can see how it must have been an overwhelming experience on the Middle Ages; perhaps one might even call it a Gesamtkunstwerk in which all the senses were corralled into one overwhelming spiritual experience. And yet, for all of this I was strangely unmoved; I lit no candles and said no prayers.