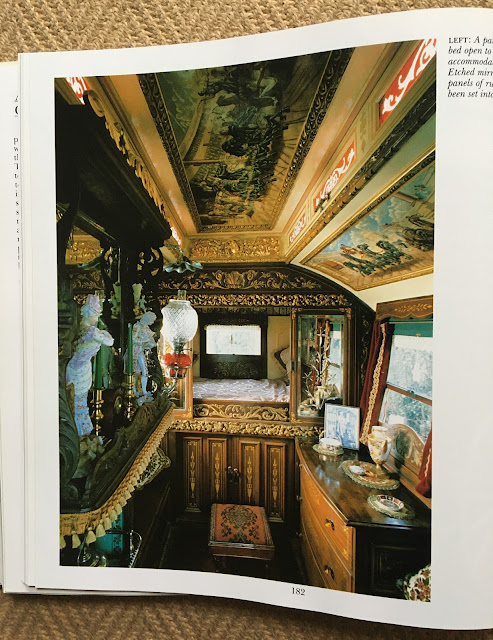

This book, 'English Style', is to be found nestling in the bibliography at the back of Ben Pentreath's wonderful first book 'English Decoration'. Although keeping a lazy eye out for other books on the list, I always felt a certain reticence about buying this book. I think I may have been put off by the images of the book on line, but I must say in the flesh this book is in many ways superb, a real delight. The photography, by Ken Kirkwood is absolutely spot-on. There are interiors by likes of David Hicks, Bernard Nevil, Charles Beresford Clarke, and Terence Conran. If I was feeling particularly cynical (which I often am these days) I might say the usual suspects. Certainly if, like me you have a (small) library of this sort of book, then you can guarantee that certain people, and certain properties, such as The Temple at Stoke-By-Nayland, will reappear with pleasant regularity. To leaven things there are, however, some new names to conjure with: Priscilla Conran, Piers Gough, Brian Henderson, Lesley Astaire, Tricia Guild, and Susan Collier (of Collier Campbell). I could go on. Anyway, in all there are some 58 entries or short chapters - short on text, but rich in photography. In addition there is both a Forward by Terence Conran and a Preface by Fiona MacCarthy. Both are good, but the latter steals the prize. Although this is a book essentially about the English house, the net is cast wide enough to include a gypsy caravan and a narrow boat. (They are, it has to be remarked, the only working class interiors.) In addition there is even, perhaps oddly, one garden. The result is an eclectic, seemingly encyclopedic book. Regardless of any claim to the latter, it is certainly an embarrassment of riches, happily swinging between austerity of Minimalism and over abundant bricolage. Minimalism apart this is essentially a conservative book, rather like Habitat (for all its vaunted Modernism). As the Introduction points out the short efflorescence of the Sixties - in its wilder moments - had little lasting influence on English style. There are no inflatable Italian furniture or Pop Art graphics on view here, and I see nothing necessarily wrong with that. Not only is there an almost innate conservatism on display but also a certain seriousness, that I suspect could verge on the high minded. An at times distant echo of 17th century Puritanism, perhaps.

'English Style', not to be confused with that excellent book of the same name by Mary Gilliatt and Michael Boys*, was first published in the US by Clarkson N Potter Inc of New York, and then in Britain by Thames & Hudson in 1984. It is the work of Suzanne Slesin and Stafford Cliff, who was also the designer. The former an American, the latter from Australia.

Slesin, a grand step-daughter of Helena Rubinstein, is a prolific writer on matters of style and design: she worked at the New York Times as both writer and editor, and is currently design editor of Conde Nast House and Garden, and Editor-in-chief of Homestyle. Among her books is a biography of Helena Rubinstein: 'Over the Top: Helena Rubinstein: Extraordinary Style, Beauty, Art, Fashion and Design'.

Cliff, as you may well remember from an earlier posts, was the designer of 'The House Book' of 1972 and the Creative Director of the Habitat catalogues in the 1970s. At time of publication he was 'Creative Director' of the Conran Group, and was the 'Project Consultant' of 'Terence Conran's New House Book' New House Book' of 1985. Slezin contributed the chapter 'One Room Living', Susan Collier 'A Sure Sense of Style'. Stafford and Slesin subsequently worked together they worked on a number of books: 'French Style'. 'Greek Style', 'Indian Style', and 'Grimsby Style'.

So far so good.

However I have a number of reservations about this book, which in 1984 was subject to a scornful and dismissive review in the December edition of the 'World of Interiors', some less trivial than others. Firstly the design. On the whole it is very good. I particularly like the use of a different textured paper for the 'supporting cast' - the introduction, the 'Catalogue of Sources', and the Index, etc. There is a logic to it. However the last two pages of the Introduction are in the same glossy paper as the 'main feature'. A small point, I know, but some consistency would be preferable. I suspect a technical explanation, which is fair enough.

My main reservation however lies with the text of the Introduction and its ambition - and, indeed, the ambition of the whole book. I realise that all books of this sort are subjective in their choices - the omitted (alas, no Angus McBean) are perhaps as telling as the included - but the authors go further than usual by attempting to cement Habitat and the whole Conran phenomenon in the mainstream of British art and design, as inheritors of the 'great tradition'. There are two problems with this; firstly the writers are too close (being part of the Conran cohort) to be completely objective; and secondly, and I think, shamefully, there is an attempt to do this by denigrating the opposition ie Laura Ashley. A tame academic from the RCA is even brought in at this point like a hired assassin to wield the knife. And that, to me at least, all seems a bit unnecessary.

Truth is, I suspect, that 'English Style' is in all but name a Conran production - at least a half a dozen of the interiors catalogued here are owned by people closely connected to TC, including the home, 'Old House, Informal Mix', of one of the photographers who worked on the 1985 Habitat catalogue - same furniture in the same positions in both publications etc.

The result then is not what you might call objective however it is a thing of beauty, and utility. A very useful visual and historical reference to an eclectic, and interesting, period in British interior design.

* Little in the way of inflatable furniture etc. there either.