And so, to the interior. This is church as cave; the place of the Nativity or the Resurrection. It is filled with furnishings, mainly nineteenth century. A treasure hoard. There is some quite extraordinary work on display. So with all this richness where to begin? Perhaps with a little chronology. It always helps. (Images in the order in which they were taken.)

There's barely a trace of either the Anglo-Saxon or Norman churches so the complicated construction history of the present cathedral essential begins c1200 with the rebuilding of the old Romanesque choir in the Early English style. Three bays of the arcade survive. The piers are complex, showing the influence of the school of West Country masons to be found, for instance at Wells and Glastonbury, (and much further afield in S Wales and in Dublin). Short and very sturdy, these piers, far more than one would think structurally necessary. The aisles are correspondingly low, cave like. The two storey Chapel of St Chad's Head, attached to the s choir aisle was constructed at the same time.

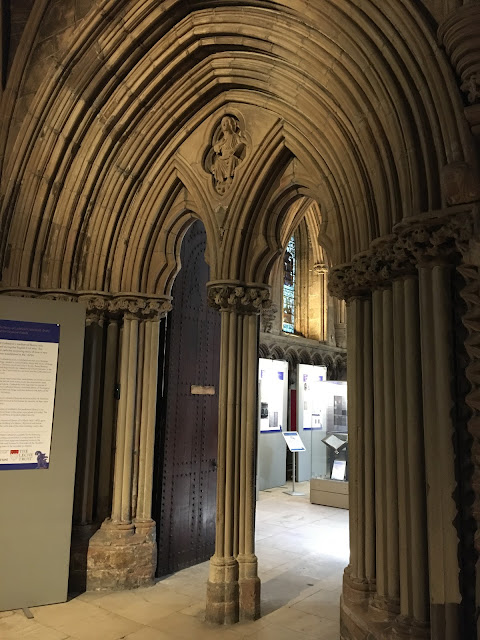

Then followed the s and n transepts in that order, both given a comprehensive working over in the late Middle Ages, and the chapterhouse & its long, dark richly decorated vestibule. More cave. The chapter house is a two storey structure, polygonal - octagonal or decagonal you decide! It's been described as both. Either way it is rather domestic in scale with little of the monumentality one associates with the great polygonal chapterhouse of such places as York and Lincoln, and none the worse for that. It currently functions as a sort of cathedral museum containing, amongst other things, two valuable Anglo-Saxon pieces of art: a fragment of sculpture - one of the scant remains of the Anglo-Saxon cathedral - and the manuscript folio The Lichfield Gospels aka The Llandeilo Gospel Book. Look for the Late Medieval painting over the entrance. Upstairs (not open to the public) currently holds the cathedral library and has done since the 18th century and the demolition of the old medieval library which stood to the north of the nave.

In the later half of the 13th century the nave was rebuilt in the Geometric Decorated style reaching the w front c1270. Some writers have associated this work with the masons Thomas, and his son William Fitzthomas who are known to have worked at the cathedral at that time.

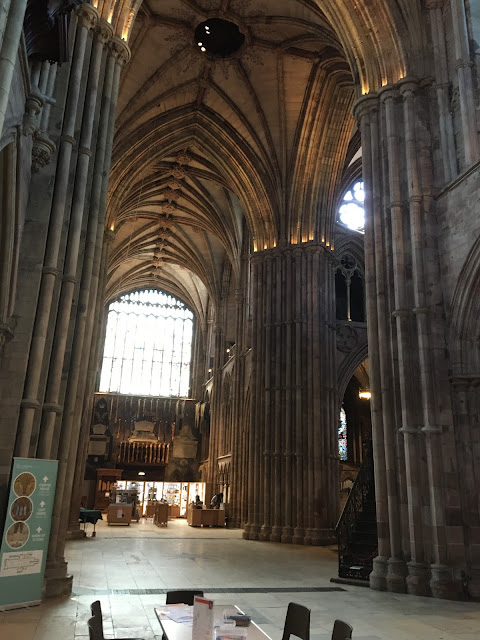

The nave is the most architecturally significant part of the cathedral, certainly its most sophisticated work. The bays are on the narrow side, well portioned, richly detailed and perhaps a little solid. The arcade takes up half the elevation. The triforium and clerestory a quarter each. That makes the triforium larger than normal, larger certainly that at Lincoln which is the ultimate source for the design via Westminster Abbey.* The clerestory - those 'spherical triangles' - on the other hand, is under the direct influence of Westminster Abbey, where a similar design is used to light the rear of the triforium. There is some influence of the Rayonnant Sainte Chapelle in Paris, but there the windows which are in the Lower Chapel there have horizontal sills, not curved as at Westminster and here. Those 'triangular' windows were already in the repertoire of French architects at the time and must be closed linked to the invention of bar tracery, for example they had been used as clerestory windows in the High Gothic Leibfraukirche in Trier built by French masons from Champagne. The form also occurs in the glazed tympanums of the w front of Rheims Cathedral and in the aisle clerestories of Le Mans and Beauvais cathedrals.

The piers, though are under the influence of a source much close to home: the choir at Pershore abbey. They are on the sturdy side, and, tend to visually block the aisles from view. The spandrels are nicely decorated with the same cinquefoil motif that appears on the w front, except here it is pierced by the vaulting shafts which run all the way to the ground, unifying the design and accentuating the verticality of what is not, as I have said in the previous post on the cathedral, a particularly tall elevation (under 60ft).

The whole interior elevation (rather like the w front) is like some highly patterned screen that keeps the eye firmly within the main volume of the nave. High above there is more patterning with a tierceron vault based on that in the nave of Lincoln Cathedral. There is a general feeling of Lincoln about the whole design, but the nave at Lincoln is more spatially integrated and structurally daring. The design here takes relatively up to date ideas and happily uses them for their decorative value.

The later nave at Worcester seems to be a variant on this design. The pier forms and the proportions are very similar.

So far so straightforward, however in the early 14th century a new apsidal Lady Chapel was constructed at a distance e of the cathedral, and, what is more, slightly out of alignment with existing e end. The difference in alignment between nave and e end can be seen in the first photograph. It is not a 'weeping chancel'; its meaning is not symbolic but simply utilitarian - the builders were merely following a bed of sandstone on top of which to construct the cathedral foundations. The design of the Lady Chapel has its origins in the Sainte Chapelle in Paris. The interior is quite good, the exterior less so. Though I haven't been able to understand why the mason varied the width of the bays of the chapel 'nave'.

Work then commenced to connect this new chapel to the rest of the cathedral. This involved destroying most of the EE choir and its ambulatory (it would have looked something like Southwark or Glasgow) and constructing a new choir and retrochoir. This was done in the Curvilinear Decorated style; the piers keep the proportions of the EE piers in the choir, the details alone being different; the repetition of the cinquefoil from the spandrels of the nave arcade is a nice touch. Above the arcade, the designer - possibly William of Eyton or William Ramsey - dispensed with the triforium altogether, reduced the inner and outer leaves of the 'mur epais'** to what amounts to a second arcade and introduced a new leaf midway between the two, pierced with vast clerestory windows, taller than the arcades below them. I wonder if the choir at Great Malvern Priory is a descendant of this sort of design.

Most of the clerestory tracery apparently dates now from Restoration period and is in the Perpendicular Gothic. I'm not sure it qualifies as 'Survival' or 'Revival'. There are eight windows on each side: the first six from the west on each side have a rather smart tracery design, quite convincingly medieval looking; windows seven have something much more mundane; windows eight are, on the s. Curvilinear (thought to be the original design), and one the N something completely idiosyncratic, which must date from the Restoration.

* Interestingly two engravings of the south elevation of the cathedral, one by Wenceslas Hollar, show the triforium glazed. If the engravings are accurate they change the whole nature of the design.

** The 'mur epais', the 'thick wall', is a building technique originating in Romanesque period Normandy. It was bought to England after the Norman Conquest and thence diffused to the rest of the British Isles. It can be likened to a sandwich: two leaves of masonry (the bread) with a core of rubble as the filling. It continued to be used right until the end of the Middle Ages, and was one of those factors that helped shape, or define, British architecture of the Medieval Period.

No comments:

Post a Comment