To the north of the cathedral, like a boat tethered to a mothership stands the Lady Chapel. It belongs to the period of Alan of Walsingham and Prior Crauden, and it is one of the greatest pieces of Medieval architecture in the kingdom. The prolonged period of construction (1321-1349) due to the collapse of the crossing tower in 1322. It is the largest Lady Chapel to come down to us from the Middle Ages, not only in England but in the entire British Isles. It could be likened to a vast reliquary though it did not hold any relic of the Blessed Virgin Mary, or anyone else, as far as I know. It stands in the tradition of the demolished Lady Chapel of Peterborough cathedral, and the Wykeham chapel in Lincolnshire. The exterior is ooltic limestone; the interior, however, is of clunch i.e. chalk, and in places Purbeck marble.

In many ways chapel is a straightforward building; a simple rectangular plan, the long sides divided into five even bays, like that earlier Lady Chapel at Peterborough, each one clearly defined by large buttresses and prominent pinnacles. It is easy to read. There is a logic to it. These side elevations are not so different from that other fenland building of this type, the little known (and very hard to access) Wykeham Chapel, aka Chapel of St Nicholas, at Weston in Lincolnshire, which was constructed in 1311 by Prior Hatfield, and formed part of the grange of the Priory of St Nicholas, in Spalding. The west façade - the one seen by pilgrims as entered and left the cathedral - is the most ornate, with rows of niches surrounding the great w window.

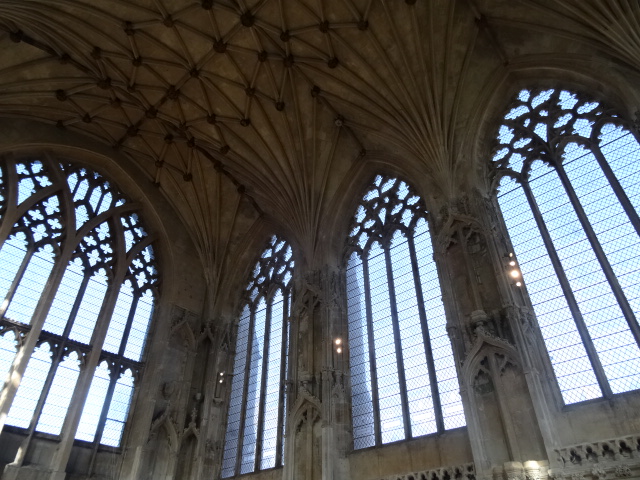

Inside, however, that clarity is clouded. Something more complex and sophisticated, and unique, than the exterior would lead us to expect, and which has elements of both the rational and the irrational. It is the irrational that strikes us first, but the best way to explain what is going on is to examine the rational first. Mirroring the exterior each bay is defined by an engaged shaft that rises from the low bench that runs along base of the chapel walls to a wide, shallow lierne vault. So far so good. Except there is an extra layer, or 'lining' of architecture - an encrustation - that forms the major decorative element, a lavish 'cage' of carved clunch that is very plastic and sculptural and ignores, if not actively contradicts, the logic of the underlying architecture. This 'cage' consists of two sections; a dado running under the windows and two tiers of tracery encasing the wall surface between the windows. The dado is the most sculptural and dynamic, with nodding ogee arches rippling in an out. The design of the dado is consistently applied around the chapel; not even the doors in the s wall are allowed to interrupt. The exception is the ruinous original reredos in the e wall. In all it creates a very self-contained space.

There is a profusion of sculpted elements to the 'cage' - rather Baroque in the blurring of categories. Standing there amid such overwhelming and sensuous architecture it is easy to understand why Thomas Rickman (1776-1841) named this period of English architecture was named 'Decorated'. There is scarcely any inert wall surface. All is movement.

Oddly, or brilliantly, each wall of the 'cage' is treated as a separate architectural element - they do not meet in the corners of the chapel. The upper sections are merely tethered to each other by diagonal ogee arches like they were the sides of a tent. (Something vaguely similar occurs in Prior Crauden's Chapel.) The corners of the chapel are thus de-emphasized, becoming shadowy voids, perhaps of infinite depth. Something similar occurs to the vault shafts along the face of walls, where they are enmeshed in tracery, hidden by ogee canopies, and (originally) by two tiers sculptural figures supported on brackets. The result of this is that the engaged shafts lose significance, so that vault appears to be a separate, discreet element.

In addition to the capitals and corbels, crockets and finials the chapel originally contained a dizzying amount of figure sculpture, perhaps uniquely so. All of this wealth of sculpture was coloured & gilded; the high vault was reportedly painted blue and speckled with stars, some of which remain. In addition, there was stained glass in the windows. There must have been moments, at least, when the chapel came close to the state of Gesamtkunstwerk.*

Today the visitor stands in the wreck. The iconoclasts have done their malignant work - the brackets are empty, the glass is clear, the stonework stripped of paint. It is the bare ruin'd choir where late the sweet birds sang. It is autumn. And yet it is still sublimely beautiful. Though of a new, different, and unintended beauty.

At the Reformation the Lady chapel, as I have outlined in a previous post on the cathedral, became the parish church of the Holy Trinity. An extra storey was added to Goldsmith's Tower to convert it to a bell tower to serve the parish. And so, it continued in its quiet parochial manner until, I think, the Interwar period, when chapel was returned to cathedral use. The monuments and memorials that had been placed on the walls were removed and the building restored. I wonder what happened to them? However, the Georgian panelling on the e wall was later used by Stephen Dykes Bower in St Etheldreda's chapel at the e end of the Presbytery. In 1945 Dykes Bower was called upon to design a new High Altar for the chapel. At first it was hoped to restore the Medieval reredos, but the cost proved to be prohibitive, and instead he designed a new 'English Altar'. And very fine it was. Alas, it was replaced in 2011 with something a lot less sympathetic. Of the statute of the BVM above the altar the least said the better.

* Enough of the sculpture survived in the dado for M R James to reconstruct the original iconic scheme. It was based upon the late 'infancy gospel' known as 'The Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew'. It deals with the life of the Virgin Mary prior to the Annunciation and the infancy of Christ.

No comments:

Post a Comment