Tuesday, 29 April 2025

Ely Cathedral: The Lady Chapel

Saturday, 26 April 2025

Ely Cathedral: The Furnishings

In recent years a number of contemporary art works have been installed in the cathedral with mixed results. The best is, perhaps, by John Maddison in Bishop Alcock's Chantry.

Wednesday, 23 April 2025

Tuesday, 22 April 2025

Ely Cathedral: The Interior

"....the inside has the greatest variety and neatness in the works; there are two Chappels most exactly carved in stone all sorts of figures cherubims and gilt and painted in some parts; the roof of one Chappel most delicately carved and hung down in great points all about the church; the pillars are carv'd and painted with the history of the Bible and description of Christ's miracles, the lanthorn in the quire is vastly high and delicately painted, and fine carv'd work all of wood...."

The interior, as you can imagine, is vast and like any Medieval cathedral not immediately or easily comprehended. It is akin to a mystery. A place to be experienced, in the which the visitor participates in the unfolding of that mystery. It is, also, not easily written about. I have found this post a struggle - how does one write about something so big and so complex?

I will start as any paying visitor does with interior of the w porch. As big as some parish churches - Early English influenced by the choir of Lincoln cathedral. Quadripartite vaulting. Arcading very elegant in contrast to the general heft of the structure. The doors into the cathedral are by George Gilbert Scott - lots of scrolling ironwork.

Through the wicket door the visitor steps into a sublimely vertiginous space - the lantern of the w tower. It is almost overwhelming, but one feels, however, the absence of that missing nw transept. The space is out of kilter. That great blank wall filling the north tower arch somehow oppressive. The w wall of remaining transept is as highly decorated as the exterior. There is no room for mural painting. Architecture, even at this stage, has become its own decoration. In the 1840s, before Sir George Gilbert Scott undertook his mammoth restoration of the cathedral, Professor Robert Willis (1800-1875) restored the transept - the ceilings of both it and the tower are his and he rebuilt St Catherine's chapel from near ruin. Since the mid-19th century, the transept has been used as a baptistry, though the font looks bereft without a substantial cover. Wondering since what, if any, was the original liturgical purpose of the w transept? And another question while we're at it: has it ever been proposed to rebuild the nw transept?

Ahead lies the immense Romanesque nave. Its height (over 90ft) makes it feel a little narrow. (It's at this moment that the critics suddenly invoke a French influence. They do the same at Beverley.) All is light, however, and there is a sense of expansion, of release to walk into this vast space. A serene space. The architecture mightily impressive and austere with little in the way of carved detail. The high wooden ceiling was decorated in the 19th century by Henry Styleman Le Strange and completed, after his death, by Thomas Gambier Parry. It is based on the early 12th century nave ceiling in the former monastic church of St Michael, Hildersheim, Germany. The shape is just perfect, a flat ceiling, like, say, the one spanning the nave at St Albans would be inappropriate, deadening. The aisles, I should add here, are groin vaulted, rather cave-like. In the s aisle of nave are two outstanding Norman doorways that gave access the cloisters. From the west, they are 'The Prior's Door' and 'The Monk's Door'. In sharp contrast to the implacable architecture around them they are richly and intricately sculpted; the tympanum of the former, for instance, contains a Pantocrator. How did it ever survive the rigors of the Reformation? Little in the way of furnishings now but in the Middle Ages two screens would have stretched across the far end bays of the nave; firstly, a rood screen, and behind that, guarding the monks quire, a stone pulpitum. The altar before the Rood also served as a parochial altar until a separate parish church, likewise dedicated to the Holy Cross, was built on Holy Cross Green adjoining the cathedral. At the Reformation this church was demolished and the congregation moved into the Lady Chapel which was re-dedicated as the Church of the Holy Trinity. The floors of the nave are, I think, Victorian.

As Celia Fiennes wrote the 'Lanthorn of the quire is vastly high'. It is indeed, floating over us mere mortals like an immense canopy or umbrella. Beautiful, serene and remote. Until James Essex re-ordered the interior in 1770 the choir ran e-w through this space within a high-walled stone enclosure. In many ways such an arrangement seems odd to us. We see the Octagon as a centralising space, so much so that it now contains a central altar as though it was some ideal church from the Renaissance, and there are historians and critics who see it as 'classical' in concept. Under the influence of Bishop Mawson and James Bentham, James Essex essentially moved the choir and sanctuary eastward, to the Presbytery of Bishop Northwold, the High Altar coming to rest against the e wall of the cathedral, though the idea for such a radical liturgical re-ordering came a hundred years before from Bishop Gunning. Writing in 1848, just as Scott was beginning his work on the cathedral, John William Hewett did not spare anyone's blushes: 'Never was there a more ill-judged step than the removal of the choir to the east end [] to give it such stinted proportions, and for this purpose to displace some of the fine old monuments, and to hide others, to obscure the pillars and above all, to erect the miserable organ gallery which we now behold, must surely be pronounced most tasteless performances...' Indeed, a lot of harm was done in the process: the old Norman pulpitum was demolished and much damage done to the monuments. However, it must be acknowledged that Essex's work on the fabric did ensure the building's survival. Hewett wished to restore the choir to original position in the Octagon, but this was not to be. Scott, in his own far reaching restoration of the mid-nineteenth century, and who undid just about all of Essex's work, merely moved the choir and sanctuary back 3 bays west to its current position.

To the north and south of the Octagon, the transepts. The oldest parts of the cathedral. It was through the door in the nw corner of the n transept that pilgrims entered the church. Their spatial experience of the interior must have been so profoundly different from ours as much of the church was simply out of bounds to them. As at St Albans they seem to have been almost an afterthought, though they provided income enough. Flooring in the s transept, at least, yellow gaunt brick. Aisles vaulted, late Medieval Hammerbeam roofs painted by Stephen Dykes Bower (?). Rather good.

At this point I entered n quire aisle and the eastern limb of the church - the quire and the presbytery. The latter is the older - but under the under the episcopacy of Bishop Northwold; EE, based on the nave at Lincoln e.g. the tierceron vault and lavish use of Purbeck marble. It was designed to hold the shrine of St Etheldreda. The quire - which originally held both the choir altar and the High Altar - is even more lavish, with lierne vaults to both aisles and 'nave'. It dates from the time of Alan of Walsingham. At some point during the Reformation the choir altar became the High Altar. From the north aisle a covered passage leads to the Lady Chapel, but more of that remarkable building in a later post. In contrast to the nave the whole eastern limb is heavily silted up with furnishings. Elaborate Victorian marble and encaustic tile floors in around the High Altar and choir, the aisles however retain old 'rustic' flooring.

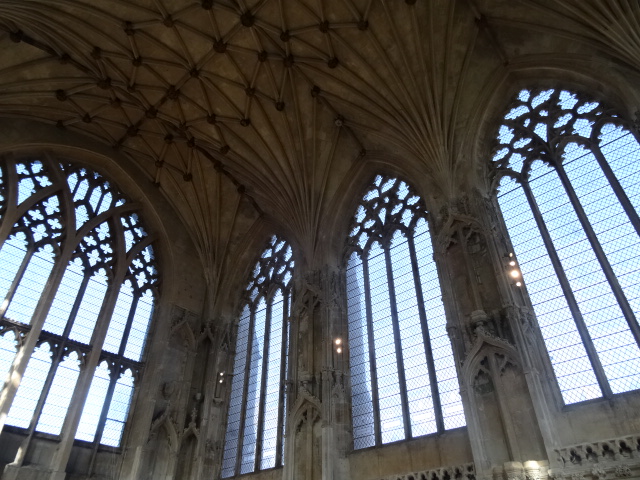

Finally at the far east end of both presbytery aisles are the fantastical chantry chapels of Bishops Alcock and West. Extraordinary confections of stone. Intimate and intense. Almost overwhelming with the profusion of architectural detailing that in a Late Gothic manner more typical of Europe obscures the logic of the architecture. The n possesses a fine fan vault with pendant, the s a net vault, profuse with Renaissance motifs.